The promise of escape from the congestion of central Cairo to a new life 40km away on the city’s outskirts is fetishised for those able to afford it. Nowhere is this more clear than on the billboards advertising real estate in “Entrada”, a housing and commercial property development in Egypt’s new administrative capital, which is currently without a name. “Welcome to a supreme community,” proclaims one. The development is touted by its creators as “the entrance to a new city, a new lifestyle, a new community and a new worldwide centre of attraction”.

The alternative capital will span 700 sq km, making it almost as large as Singapore, and is intended to house a total of five million people. The plan shows an expanse of high-rises and residential buildings as well as a “government district” all stationed around a central “green river”, a combination of open water and planted greenery twice the size of New York’s Central

The project is designed to wipe clean the problems of Cairo, and build a glistening new future. Most government buildings, as well as those occupied by the Egyptian president, Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, are scheduled to move there in June 2019. Foreign embassies are also encouraged to relocate, and businesses will be lured to a central business district of 20 Chinese-built skyscrapers. But what will happen to the old city once the new capital takes root?

If the government’s plans are successful, the move will leave behind a network of empty buildings, all owned by the same umbrella company as the new capital, and for which there is currently no plan. For the government, the new administrative capital represents a fresh start – but one that will draw wealth from the existing capital.

During a visit to the site last October, journalists were invited to view the construction of Egypt’s largest church, a new cabinet building, and stood looking at a stagnant future ornamental pool as a pair of fighter jets conducted a ceremonial flyover. Pictures of Entrada show spacious villas next to snaking pools of water and advertise their proximity to the development’s 4km of theme parks and so-called natural terrain. A two-bedroom apartment – with “a view of water”, private gardens and a maids’ room – is listed for around £45,000.

The spokesman for the project, Khaled El-Husseiny, resisted questions about the quantity of affordable housing available in the new capital and the average price of real estate. “Forget the numbers, they’re not important and not fixed,” he said, frustrated. “We have a dream, and we’re building our dreams now.”

Last month, inside the glass-walled offices of the Administrative Capital for Urban Development (ACUD), the company overseeing the project, El-Husseiny attempts to explain. ACUD is 51% owned by the Egyptian military – El-Husseiny is a former major general – as is the land for the new capital. The remaining 49% of ACUD is controlled by Egypt’s ministry of housing. El-Husseiny says it not only acts as an umbrella company to control the construction of the new capital, but after its completion will also operate the vacant buildings in Cairo.

“For example, the ministry of housing owns a building or many buildings in downtown Cairo,” he says. “I will give a new ministry building here, a smart and connected one, air-conditioned and up to date, and we at ACUD will take the old one. We are establishing a new company just to control all the buildings that we will receive from all the ministries.”

The future of the many buildings that make up Egypt’s sprawling state infrastructure, mostly situated on prime real estate in central Cairo, remains uncertain. “We have no plan as to how to invest in these buildings, but we will fix it and figure it out,” says El-Husseiny. “Maybe we can make them into hotels.”

Profits from these vacated buildings will then feed back into the ACUD. But it is also unclear just how much money is being sunk into the new administrative capital. It was given an initial estimated cost of £30bn in 2015.

“There is no total budget,” says El-Husseiny. “It’s a big one, a great one, but we must also calculate the cost of building infrastructure.” He adds that the ACUD was founded with a cash injection of 204bn EGP (£8.5bn) from the ministry of defence and the ministry of housing, but emphasises that the project will continue without further delay

There are two kinds of budget, he says: “The budget according to the documents and the actual budget they have to pay.” He says the ACUD has already repaid 20bn EGP to the banks, although the source of these funds is unclear, as is who will ultimately pay for the rest of the sparkling buildings shown in the plans.

El-Husseiny stresses the budget for the new capital will be settled on a “case by case basis” as each part is constructed. The governmental district, for example, will cost 40bn EGP. – By way of comparison, Egypt accepted a $12bn (£8.8bn) emergency loan from the International Monetary Fund in 2016.

The new capital will also draw on Cairo’s much-needed resources. Two water stations will pump an estimated 200,000 cubic metres of water per day, siphoning water from nearby satellite cities. Once the project is completed it will use an estimated 1.5m cubic metres of water per day.

“In Brazil it was Rio and it became Brasília – we need this. It costs billions, we know, but we need it,” says El-Husseiny, referencing Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa’s landmark project to build a new capital in Brazil, now regarded as a symbol of the failure of urban planning and inequality. It is hoped Egypt’s new capital will house almost twice the population of Brasília, while paradoxically appealing to incomers as a way to escape Cairo’s crowded street life.

There are few guarantees the high cost of housing will allow anyone other than the upper crust of Cairenes to populate the new capital, and the project risks becoming a lucrative but empty building project similar to the “ghost cities” of China. Government workers will receive an estimated 25% discount, but with the average price per square metre estimated by El-Husseiny at 8000-9000 EGP (£323–363), it is far beyond the means of the average public sector worker, whose weekly wage was just 1154 EGP per week

There is no doubt that Cairo’s rapidly expanding population desperately needs housing. The number of inhabitants grew by half a million in 2017, making it the world’s fastest-growing city. Greater Cairo, now a megalopolis, housed 22.9 million people as of mid-2016 and is projected to contain 40 million by 2050. But the city is already ringed by a large collection of half-empty planned towns, each a failed monument to their developers’ inability to draw the bulk of the population away from downtown Cairo.

“Cairo’s already-existing desert ‘cities’ mostly serve the much higher end of the spectrum economically,” says Mohamed Elshahed, an Egyptian urbanist and the editor of the Cairo Observer. “All of these include social housing as part of their developments. But that doesn’t mean it won’t be a tiny per cent of a much larger speculative real estate project, which is what this [new capital] is really about.”

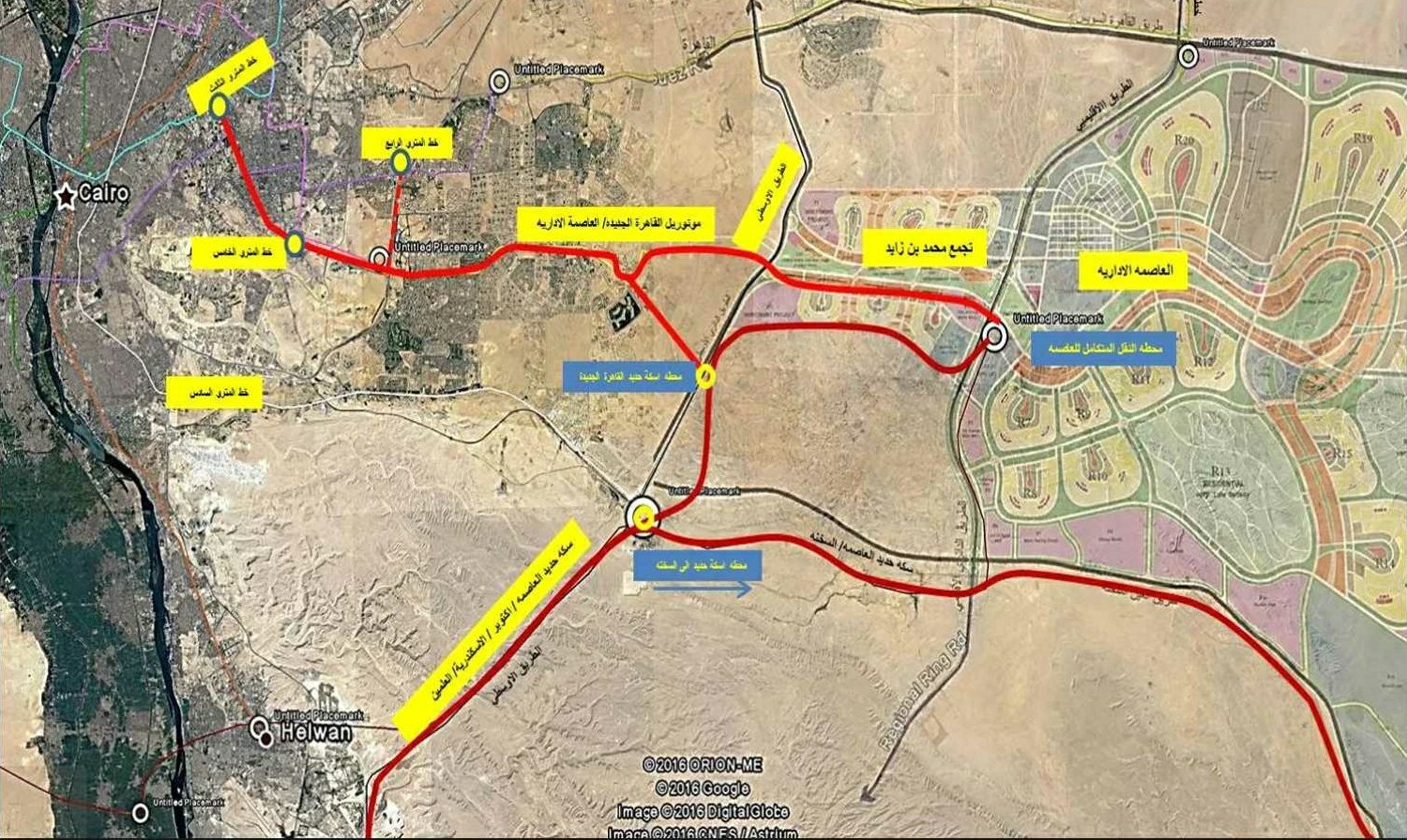

Workers unable to afford to move to the new capital may be able to use the proposed electric train and monorail to get to work, but there are no guarantees that these will be competitively priced either. “In order for the new capital to succeed, if the goal is to reduce congestion, it doesn’t come simply by moving a few thousand employees,” says Elshahed. “Most government employees don’t own private cars, so it’s not like it’s them congesting downtown Cairo.”

El-Husseiny, however, is determined that his vision alone will entice enough new residents, including foreign embassies and those working there. “We will give them benefits not available in the old Cairo, wide streets and a smart city,” he says, going on to outline something quite dystopian: “A smart city means a safe city, with cameras and sensors everywhere. There will be a command centre to control the entire city.” A spokeswoman for the British Embassy in Cairo says that while the Egyptian government has located space for embassies, they are currently “assessing the move”. Other embassies contacted by Guardian Cities were hesitant, but unwilling to discuss this publicly.

“Cairo isn’t suitable for the Egyptian people,” says El-Husseiny. “There are traffic jams on every street, the infrastructure can’t support the population, and it’s very crowded. Without any specific masterplan, it has started to become ugly … there’s no humanity.”

There is no doubt that Cairo’s congestion makes residents fantasise about escape, although wide streets, double-glazed windows, open water and pruned topiary seem more like the dreams of suburban London or Chicago than ideas well-adapted to the desert plain.

But El-Husseiny is adamant. “We need a landmark, a new capital. We have the right to have a dream and this is our dream.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here