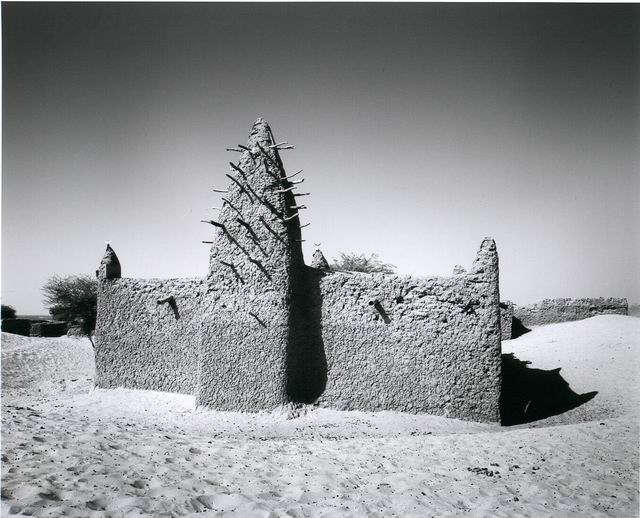

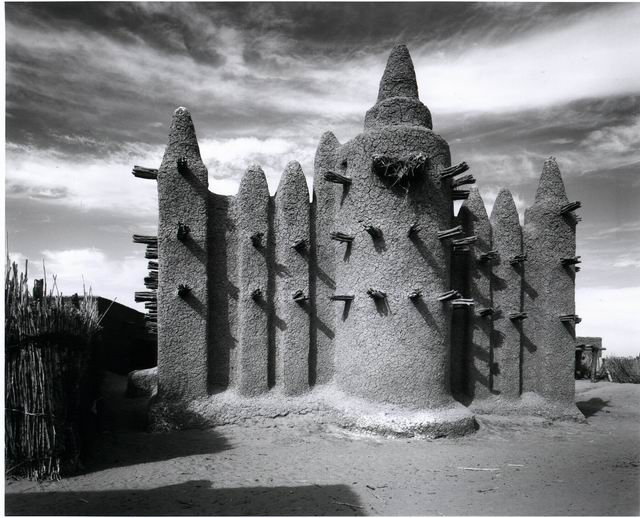

West African mud mosques satisfy all the standard expectations of mosque architecture — with the qibla marked buy its mihrab, minarets, interior spaces delineated by transverse naves and aisles of columns — while at the same time abstracting these forms that were canonized in the regions of the post-Byzantine, early Islamic Empire. Sebastian Schutyser’s photographs capture and perhaps exaggerate the otherworldly quality of Mail’s mosques. By extracting people and surrounding buildings from the frame the eye is drawn to the materials and forms, which adhere to what is a unique design program particularly suited to the region, but that still serves typical mosque functions of worship and gathering.

Mali’s mud mosque architecture is directly related to local domestic architecture. Materials are selected both for their economy and their appropriateness for the remarkably hot climate. Earth used to create mud mortar and mud plaster, and minimal palm wood for scaffolding and roofs, as timber is a rare and costly commodity, compose the forms.

Walls are thick and tapered, to both protect the inside from the heat and support the often two story structures and the roof. During the day, the walls absorb the heat of the day that is released throughout the night, helping the interior of the mosque remain cool all day long. Some structures, for example, Djenné’s Great Mosque, also have roof vents with ceramic caps. These caps, made by the town’s women, can be removed at night to ventilate the interior spaces. Masons have integrated palm wood scaffolding into the building’s construction, not as beams, but as permanent scaffolding for the workers who apply plaster annually during the spring festival to restore the mosque. The palm beams also minimize the stress that comes from the extreme temperature and humidity changes typical of the climate. Towers are often topped with a spire capped by an ostrich egg, symbolizing fertility and purity.

Sources:

Maas, Pierre. 1990. Djenne: Living Tradition. In Aramco World Magazine January-February 1990. Robert Arndt (ed). Houston: Aramco Services Company.

Snelder, Raoul. 1984. The Great Mosque at Djenne. In MIMAR 12: Architecture in Development. Singapore: Concept Media Ltd.

https://archnet.org/sites/4072

Dramatically photographed in black and white by Belgian photographer Sebastian Schutyser between 1998-2002, these stark images present the mosque as object. The collection gathers some of the finest adobe mosques of the Niger Inner Delta. Sebastian Schutyser tried to photograph every one of these mosques as an individual structure, with a character of its own, using the shadows and contrasts of the black and white image to highlight the contours and form of the structures. The uniform approach stresses the great variety in style, and the uniqueness of each mosque. Africa has always known an oral tradition in literature. This rich tradition is in peril, as modernity drives the younger generations away from the elderly. Fortunately African authors such as Hampate Ba (Mali) started recording the legends and history of their people. From him, comes the saying that “… every time an old man dies in Africa, a library burns down”. Adobe is the architectural equivalent of this oral tradition. This living architecture is vulnerable because it is made of “soft” material. With this black & white collection the photographer tries to record the poetic force of these mosques, and preserve their image for future generations.

https://archnet.org/collections/16/details

Subscribe

Login

0 Comments